In most ways, my story is much the same as those of my generational cohort: born into a world humming and crackling its way through the greatest economic boom ever experienced in living memory, and coming of age against the backdrop of unceasing violent asymmetrical conflicts over resources and geopolitical influence, burgeoning socio-economic inequality, and increasingly hard-to-ignore environmental and climatic instabilities. I was born into the War on Drugs and graduated into the War on Terror, and now it seems we're getting locked into a War on Each Other (but isn't that always how it's been?).

When I entered college, the state and federal governments threw money at me. I was the smart poor kid, the one who would have been a conservative's wet dream of pulling himself up by his bootstraps and making his way in the world entirely through his own gumption and fortitude. Counselors encouraged me to 'pursue my passion', because smart people like me tend to do well when they do that (that is not universally true).

But being the oldest son of a family hit hard by the bitch-slap that globalization inflicted on once easily-available entry-level jobs requiring no college degree, I initially set out to pursue nursing, because I never wanted to be poor again. Instead, I got my ass kicked in general chemistry and chose to pursue anthropology instead (which was what I read when I was procrastinating my way through my undergrad years). I decided being poor wasn't so bad, because I had managed to be both happy and poor at the same time.

The most radical act a young person can take is to be happy --- we live in a world that constantly pokes young people to do more, to aim higher, to work harder, underpinning it with the assumption that if we don't, we'll die poor and lonely. Being happy means not listening to those voices, and instead, doing whatever it takes to maintain and increase your happiness. For me, it had little to do with money and a lot to do with impact and life satisfaction. That's a big deal for me, since financial security and prosperity are increasingly out of reach for most people of my generation.

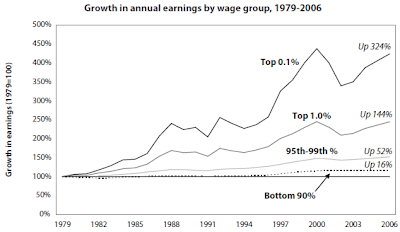

So I graduated in 2009, looked around, saw forty-somethings with years of experience in supposedly recession-proof STEM fields begging for entry-level jobs, said 'hell no', and did a lot of volunteering and protesting for two years before deciding that wasn't something I could do for the rest of my life (e.g. couldn't pay the bills and wasn't getting any satisfaction out of it), and so here I am, in grad school, and while the economy's 'picking back up', it's only really benefiting those who were already set-up before the Great Crash of 2008. I sometimes wonder what the fuck I'm doing in grad school, and remember that as a grad student, I am much better off than I was as a graduate struggling to make ends meet while sharing an old house with five other people. But part of that is thanks to my student loan debt, which while below the national average, is still keeping me up at night.

We, the teeming millions of young people trying to find our place in the world, are in a difficult place relative to those born even a decade before us: those older than us offer us thought-stopping chunks of advice like "stop feeling sorry for yourselves" and "manage your expectations", forgetting that we grew up under "chase your dreams" and "work hard and you'll succeed". It wasn't our peers who started that silliness; it was our elders, who conveniently forgot all that once the Great Recession of 2008 rolled in.

Let me get this straight: I worked my ass off, full-time while taking full-time course loads. I did not waste my early adult years partying. That was for kids who could afford to not work on Friday nights. Not me, and not many others. The only young people who have it easy are those whose lives are supported and subsidized by the inherited hard work and sacrifice of older generations. It's a mark of the privilege enjoyed by many among the older generations that they don't have to think about the struggles of the young, while we the young cannot afford the luxury of not thinking critically about our situation and placing it into context.

|

| Context: we've been in this situation before. |

The older generations need to stop painting the younger generations with a broad brush, because frankly, that kind of thinking is nothing more than masturbation: satisfying in the short term but accomplishing nothing over the long term.

But the same is true for the younger generations: I mistrust Baby Boomers because they were the grandparents who hurt my mother, the bosses who screwed my family over, the oblivious old farts in carbon-vomiting land yachts trying to run me over on my bicycle, the elected officials giving tax breaks to their peers while turning a blind eye to anyone who isn't part of their tribe.

In short, Baby Boomers are power, and I mistrust and resent power because I have more often than not been on the receiving end of abuses of power. I have particular contempt for the class of Baby Boomers who live their lives in comfort while offering shitty advice with a straight face, as though the economic climate of the US was in any way recognizably similar to the one we, the 80 million young, must contend with today.

So what do we do about it? I have a couple of ideas (a topic for a later post), but I welcome input from anyone else, both old and young.